Deep Roots: Clothing as Culture

Humans are the only animals who wear clothing—not just for warmth and elemental protection, but for expression of identity. Historians tell us that this has been true from the earliest records of human behavior.

Even before the inhospitably frigid weather of the Ice Age, which forced humans to find ways to stay warm, early humans developed tools like sewing needles. Around 30,000 years ago, during the Stone Age, the emergence of the eyed needle enabled people to survive the Siberian winters.

But as climates grew warmer, clothing remained essential, and evidence emerged of its social and spiritual meaning. As Gilligan notes, “decoration may have even motivated Paleolithic tailors.”

One of the oldest known woven garments—or, the ultimate vintage dress—is the Tarkhan Dress. Discovered in an Egyptian tomb, the 5,000-year-old linen garment likely held both social status and ceremonial significance. “Beautifully stitched and pleated, it signals the complexity and wealth of the ancient society that produced it,” Traci Watson wrote for National Geographic.

In the pre-colonial Philippines (900 C.E.–1565), the tapis—a woven skirt—served as both a spiritual and social marker. According to a review article published by the Nancy M. Bruces Center for Design and Material Culture, among the Ifugao people, elders wove intricate patterns such as the tinaggu, which represented deified ancestors and embodied meanings of intergenerational protection. This visual language, deeply embedded in community tradition, has been passed down for generations and still exists today. As one researcher described it, the tapis is “a unique product of a longstanding cultural legacy of resistance.” Weavers approached their craft with expertise and deep care—threads were precisely spaced to avoid flaws in the fabric. Natural materials, such as bark cloth, were commonly used in the making of these garments.

In pre-industrial Japan, textiles were often made from bast fibers—materials extracted from the inner bark of native flora. Gathering and weaving these fibers was a time-intensive task typically performed by women with both the materials and the making of clothing were preserved in communal knowledge, and garments were treated with care, intended to serve many forms and functions throughout their lifetime.

Rooted in Buddhist beliefs, the Japanese philosophy of mottainai—often translated as “waste not, want not”—shaped how people related to their clothing. This mindset is reflected throughout Japan’s material history. In Edo (modern-day Tokyo), for example, a cotton kimono would be worn until it softened with use, then repurposed into pajamas, children’s clothing, or cleaning cloths—and eventually burned for fuel or used as fertilizer. Throughout each stage of its life, the garment remained part of a shared thread of knowledge—people understood where the material came from, who made it, and how it would return to the earth.

During the Inca Empire (1438–1533), textiles worn only by those affiliated with the state often featured geometric designs known as tocapu. These motifs likely functioned as a visual language tied to status and place of origin; in one notable historic chronicle, they were called “dress or clothing of the Inca made with a thousand wonders.”

A small selection of many examples through recorded history, these phenomena show how “threads were among the earliest transmitters of meaning,” as noted by 20th century German textile artist Anni Albers.

The Shift from Handmade to Mass-Produced

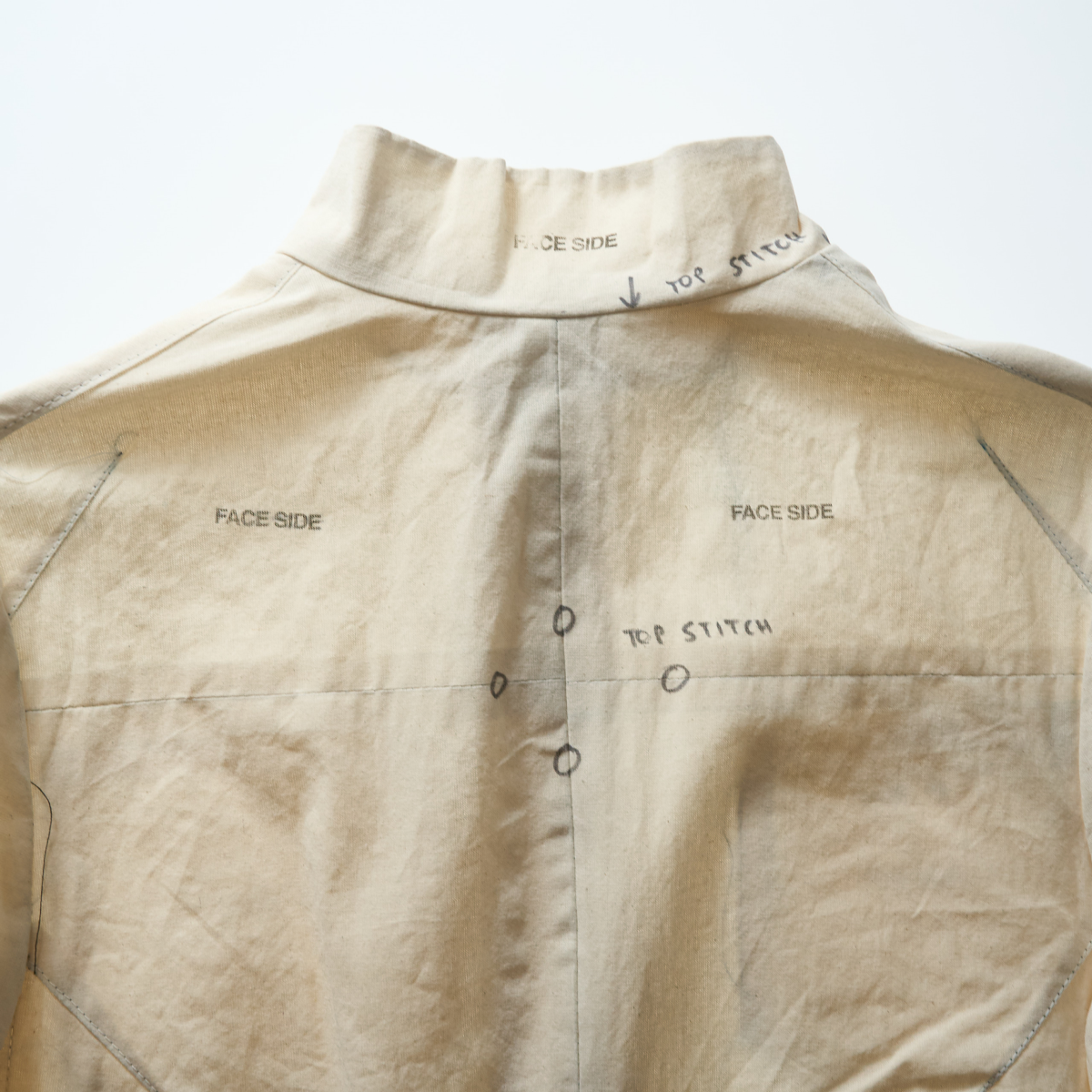

Before the Industrial Revolution, garments were handmade, worn often, mended when needed, passed down between generations, and discarded with care. Clothing was not just owned—it was stewarded; slowly, intentionally, and often with personal and communal value. But the rise of mechanized textile production beginning in the 18th century dramatically shifted the way we relate to clothing. The era of cheap, accessible, and disposable clothing had begun.

Machines like the Spinning Jenny, the Power Loom, and the Cotton Gin made production faster and cheaper, displacing skilled artisans and replacing care with convenience. By the late 1700s, a calico dress could be sewn in under an hour by machine—compared to six hours by hand. The connection between people and their clothes began to erode as industrial systems prioritized quantity over craft.

With the textile revolution came a massive cognitive shift toward material value. Between 2000 and 2015, global clothing production doubled, while the average number of wears per garment dropped by nearly 40%. Fueled by accelerated fashion cycles, constant seasonal drops, and lower price points, this overproduction led to overconsumption—a shift that almost depends on a lack of emotional connection between garment and wearer.

In pre-industrial times, that connection was inherent. People knew where the material for their garments came from, who made them, and how long it took to turn fiber into wearable form.

That intimacy has, largely, been lost. Today, the creation process behind our clothing is obscured. We may not see the materials extracted from our Earth or the hands that crafted each piece, but they’re still there—just hidden from view.

And when we no longer carry this kind of knowledge, it becomes easier to take our clothing for granted.

Today, over 100 billion garments are produced each year. Many are worn only seven to ten times before being discarded. This linear system—make, wear, discard—was not designed to be sustainable.

Future Threads: Reclaiming Value

Our methods of clothing have changed. But the potential for meaning remains.

What if we treated our garments with the same care and reverence they once held? By understanding how they were made and how they will move through the world, we can change their perceived value and begin to change their linear path, away from landfill.

We won’t arrive at a circular economy only by changing systems—we also have to change how we see our clothes. When we understand what went into making them and what they carry through time, we reconnect with them as transmitters of cultural and environmental meaning—not just consumables. This way of seeing supports the goals of a circular system for clothing: worn longer, cared for with intention, and renewed into new forms at the end of their lives. As the Ellen MacArthur Foundation writes, “clothes, textiles, and fibres are kept at their highest value during use and re-enter the economy after us, never ending up as waste.”

This isn’t a new idea—we’ve practiced it for most of our time on Earth. History shows us that clothing can be passed down, repaired, and eventually discarded with care and respect. It’s a mindset we can return to: one that treats clothing not as disposable, but as something worth honoring through every stage of its life.

- We can begin by asking these questions:

- Where did this garment come from?

- What is it made of?

- Who made it?

- How does it relate to the story of my life—and how can I extend its use?

- What happens to it when I’m done with it?

The only real difference between “waste” and “worth” is our perception. It’s time we shift it.

We believe in building a future where the end of a garment’s life is not the beginning of ‘waste’, but the moment of transformation into something new.